Ever since I was a little girl, I knew I was just like the other girls. I made friendship bracelets and painted my bedroom walls pink and learned ballet and built mansions on sims using ‘motherlode’ and ‘rosebud’. And then, one day early in my adolescence, I was home sick from school, and my mum rented Mean Girls from Blockbusters on the corner. That was how I discovered lip gloss. It unleashed something in me. Some curated millennial-pink dream that I couldn’t un-see. Shortly after came the seminal text: Devil Wears Prada. I was dazzled. That’s when I decided what I wanted to be when I grew up. I wanted to work in a magazine.*

But I wasn’t interested in fashion. I didn’t have the eye for it. (Honestly, I still don’t). I was interested in language. In cultural analysis. In stories that cracked the world open. In words that reflected culture back to itself on glossy, curated pages. I wanted to strut into a high-rise building wearing stilettos, holding a latte, way before I knew what lattes tasted like. It was the most cliched dream. Like I said: just like other girls.

Fast forward a decade: I did work in magazines, for a while. I freelanced, post-pandemic, working mostly from home. When I did go into the office, I wore trainers. I drank coffee not because I thought it was chic (it wasn’t), but because I needed it. It was fun and exhilarating and exhausting. And then I stopped. Because I wanted to write; because I wanted a different kind of career; because of so many things. I started writing this newsletter at around the same time that I stopped working in magazines. A part of me was heartbroken. A part of me was relieved. A part of me couldn’t believe that anyone actually wanted to read my writing.

But I’m still completely and totally in love with print media. There’s just something so special about reading something from a page, instead of a screen. About treasuring not just the look of something, but the feel of it, too. Is there anything more chic, more effortlessly cool, than reading an essay in print? (The answer is no).

And I’m not the only one. Last year, several print magazines came back from the dead: Nylon, Life, Swimming World, Saveur, NME, Sports Illustrated, Vice, to name a few. At the same time, some publications are venturing into print for the first time (like The Onion), whilst other print-forward indie publications are thriving (think: Apartmento, Kinfolk, Byline). Several publications commented on the resurgence: The Times published a piece entitled ‘Why Print Media Is Coming Back From The Dead’, Bloomberg wrote on ‘The Print Revival of 2024’, whilst The New York Times wrote about The Onion’s foray into print.*

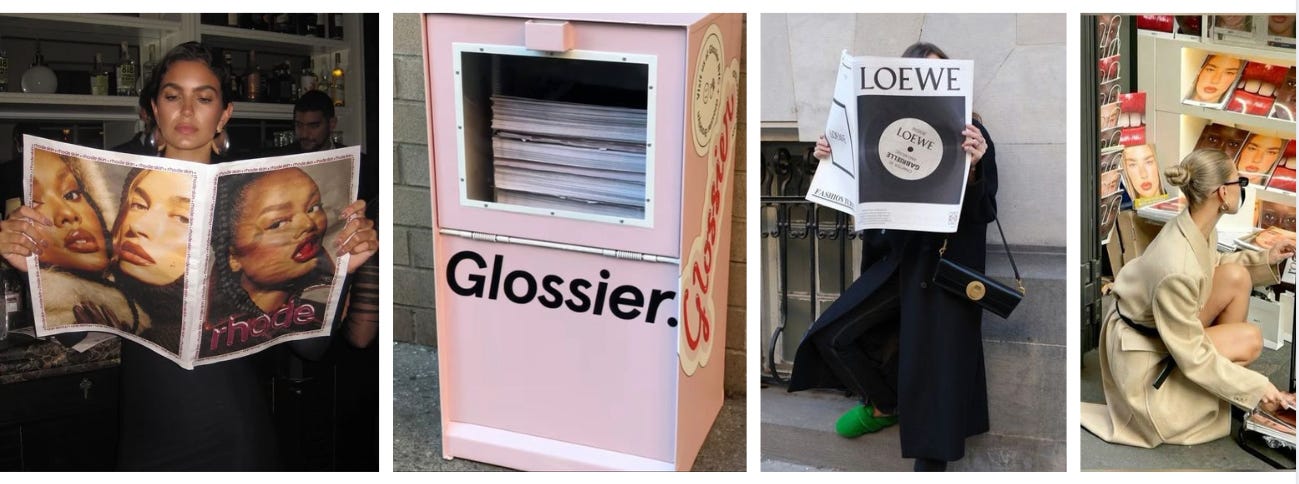

At the same time, some of the most inventive (and attention-grabbing) marketing campaigns in 2024 were print-based. MERIT partnered with The Gentlewoman to curate a magazine called Retrospect, to launch their first perfume. (I was gifted both the perfume and the magazine and loved them). REFY launched a beauty Kiosk in Paris, Rhode created a Lizzie McGuire-type newspaper, Hinge distributed a ‘No Ordinary Love’ zine, Jacquemus introduced a pop-up newspaper, Glossier launched a zine alongside its SoHo pop-up, and Lush continues to produce their newspapers, which you can pick up for free in-store.

In 2025, print is the ultimate chic accessory. Magazines are cool again. But why? Well, here are my two cents.

How you spend your attention, in 2025, is one of your most valuable assets. If you’re watching/reading/listening to something and you’re not paying for it, then you are the product. We are stuck, like rats, in a self-reinforcing loop of dopamine addiction as we swipe from video to video, app to app, hoping to get that first rush of good content. Our attention is constantly up for manipulation, for being grabbed: by breaking news and Instagram stories and TikTok notifications and billboard ads and Spotify ads and everything feels urgent, all the time. As Daniel Immerwahr writes for The New Yorker, “Our attention is being redirected in surprising and often worrying ways.” In the piece, Immerwahr posits that it’s not an attention deficit that’s the real concern – it’s what we choose (or don’t quite choose; what we’re manipulated into choosing) to focus on that really matters. And it’s this mode of thinking that has us racing to download app blockers, to invest in five-minute meditations through the Headspace app, to switch our phone on Do Not Disturb and engage in the kind of media that exists on paper, as opposed to a screen.

Instead of ever-changing trend cycles, print media is slow. It’s quiet. It croons ‘romanticise a quiet life,’ in Phoebe Bridgers’ breathy voice. It suggests lilting candles and soft quilts and tiny cups of steaming espresso. In the place of randomised ads for ‘weight loss products you definitely need’, print media is a Pinterest board that you didn’t have to make. Every inch of the page has been designed, pored over, loved. Instead of a screen, you get the tangible equivalent: soft pages to be earmarked, by-lines in which to write your own notes. It’s the vinyl of Spotify, the film camera of the iPhone. Instead of the dystopic present, with Trump’s stupid hairstyle and nonsensical announcements all over your feeds, it reminds you of a simpler world. Of red-pink nostalgia, lip-gloss girlhood. Elle Woods in a nail salon. Go on, print whispers, go back in time. We dare you. Instead of scattered feeds that range from how to cook a boiled egg to a faux-fur-clad celebrity, stilettoed on a red carpet, you have curation. Images and words and illustrations and columns that work together to create something beautiful. A whole, artistic piece. A collectable item. Something for your coffee table. ‘Have you seen this issue?’ you might ask a friend. ‘Here, you can borrow mine.’

Last summer, I made a TikTok video about Nokia relaunching its iconic 320 phone, in which I predicted the rise of dumbphones – and being offline in general – as a status symbol. A-Listers (and the super-rich) in the future will be the only ones capable of not having a phone – because they’ll have teams to do that for them. Being offline will, over the next few years, become the ultimate luxury. And the same can be said for print media. As Mel Ottenberg, editor-in-chief of Interview magazine said in New York Magazine: “Print is a luxury item.”

Of course, there’s an element of this word which implies luxury in the fashion sense: glossy, thick pages. Fashion spreads with designer brands and stylists and artistic directors. But I mean it in the other sense: something only obtained rarely, in the glimpses of quiet between moments of scrolling. A feeling of comfort, of elegance. An inessential, desirable item that is hard to obtain only in that it is hard to tear ourselves away from the screens on which we’re all so reliant.*

And so, the rise in print media can be seen as a direct response to the reality of being online. Fleeting trend cycles, untouchable objects on Instagram feeds, a distinct lack of community, of visual appeal. “Buy a magazine!” we think, “it’ll cure your digital fatigue!” (No, really, it can). This is your chance to choose something on which to spend your attention. To pick something out as opposed to swallowing whatever is served to you algorithmically. To curate your own taste. To take a deep breath and savour it. To learn something new. To savour the feeling.

This is what I tell people, when they ask why I’m launching a zine. I say: there’s a print revival, right now. And I’m obsessed with it.

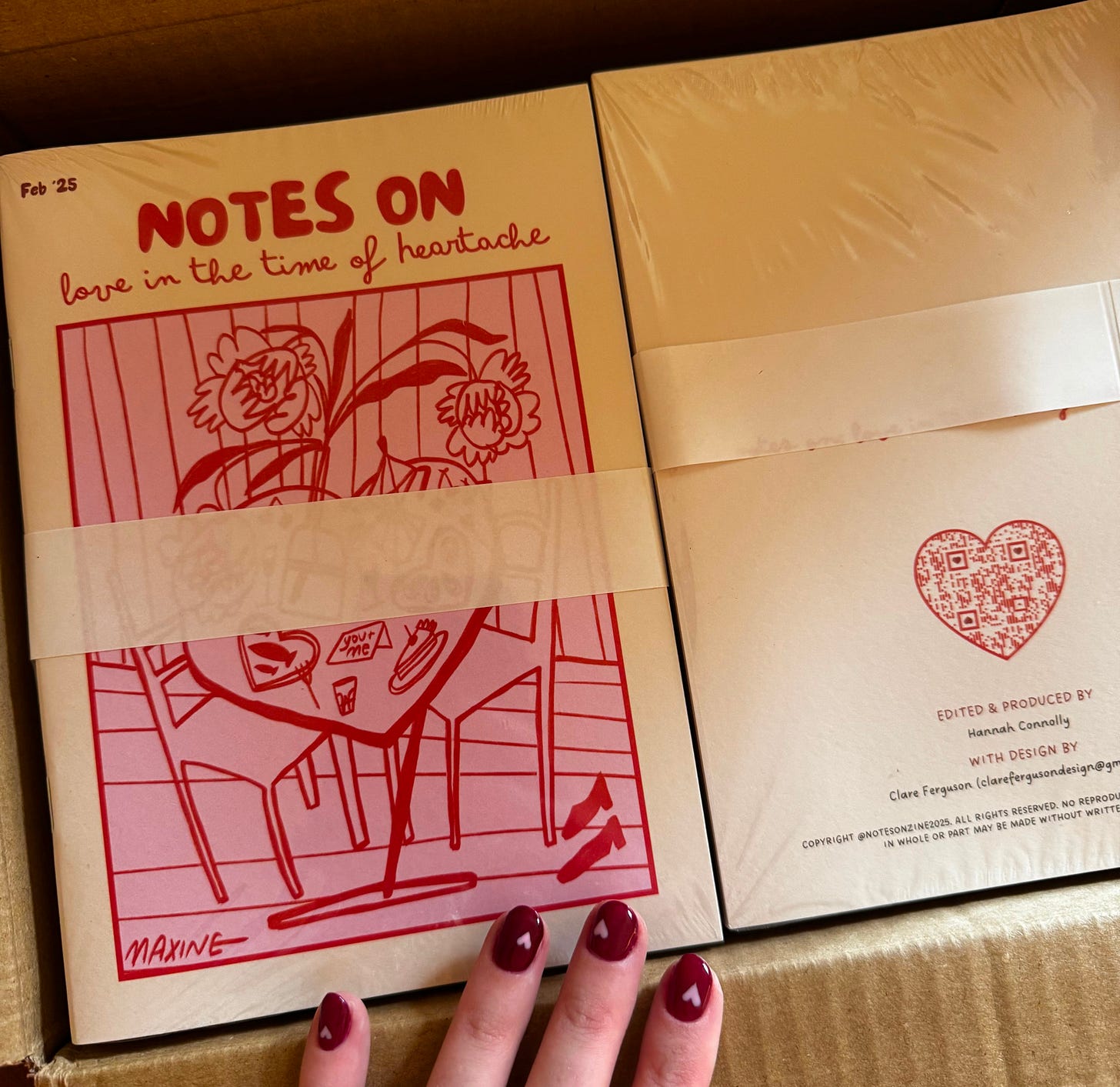

When they ask what the zine is about, I say: it’s called ‘Notes On: Love in the Time of Heartache’, and it’s a publication about finding pockets of love and joy in a world that can sometimes feel dark. With essays and artwork from writers and artists I admire from different corners of the internet, this zine is a love letter from us (artists, dreamers, hopeless romantics) to you (whoever you may be). It will be delivered in a red envelope, like a love letter. Because people also love receiving things in the post.

And then I say: People want magazines. They want to consume media that isn’t blue-lit. They want to disappear into the secret gardens of someone else’s creative vision, if only for half an hour. They want to escape, and be inspired, and feel seen, all at once. They want to feel something real – both physically and emotionally. They want to escape the algorithm. In the words of Miranda Priestly: Everybody wants this.

And then I smile, or laugh, and I hope there’s a twinkle in my eye, so that whoever I’m talking to knows that I’m not serious, even though deep down, we both know I actually am.

P. S. In case you’re interested: you can buy one here.

Footnote 1: I also wanted to be an author, and work in a publishing house, and be an editor, and a TV producer. At that age, ‘what you want to be’ changes as frequently as you re-organise your room. (For me, that was a lot. In fact, almost daily).

Footnote 2: Of course, this comes at a tricky time for media in general, with beloved publications like Vice.com shutting down and waves of redundancies hitting legacy brands like Hearst and Condé Nast. As Amanda Mull wrote for Bloomberg: “The old model of print is certainly gone … But an opportunity remains for magazines, business models be damned, and some publishers and brands seem to be figuring it out.”

Footnote 3: Social media, I think, is playing a very important role in all of this. As @thotsandprayers said in a TikTok video: social media is “poised to become the discovery point [of print media]” which is particularly interesting “especially when you think about it in the context of like the rise of online was really kind of why print media had this big shuttering, but could it be the thing that kind of brings it back?” Kinfolk is a great example of this. For a print magazine to be successful, right now, it needs to have an in-depth understanding of the social media landscape – as well as incredibly strong branding. They need to understand that their discoverability will come through social media, and lead to sales of their physical product.

I'm a print media girly and have bought magazines religiously since Mandy and Judy and Bunty when I was 10. I progressed to Shout and Mizz and then Bliss and Sugar then Just 17, teenvogue, ellegirl before finally stepping foot in to the glossy jungle of vogue, Elle, she, instyle et al. I worked as a marketing assistant then copy editor then girl about town for a Manchester based lifestyle glossy before the recession when I was made redundant. In time many of my favourites shut down. Now, I still buy my monthly magazines. Red is a favourite and I recently completed a 20 minute survey for it feeding back as my love for it has started to fade as it falls out of touch with its readers cost of living realities. I also buy Good housekeeping, Woman and Home, The Simple Things (my favourite), grazia, hello fashion. If I make it out of my village and in to the big smoke of the city, I pick up the matte covers of more indie brands. Carrie Bradshaw once said she skipped lunch to buy vogue because she felt it fed her more. Hyperbole but also oh so true! I'm a fashion lover (if not a fashion girly myself) and so I pore over images of beautiful things and imagine how I can add a little of that beauty and glamour to my own style and life in my own way (and on my own budget!)

I'm so glad print is back. It's been a friend since the very first issue of Mandy and Judy! And I cannot wait for Notes on Love in a Time of Heartbreak! Xxx

“Go on, print whispers, go back in time. We dare you.” Yes. Please. ♥️💌